Commentary on the Australian Broadcasting Corporation’s Production of:

“The Story of Australian Art”

text by Robert Smith, production, photography and coding by N. Stanley 2014

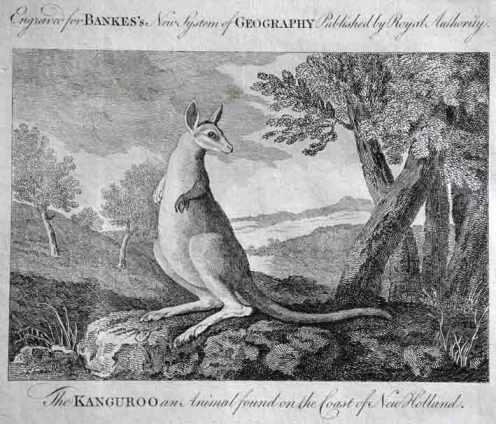

After George Stubbs (1724-1808) The Kanguroo, an Animal found on the Coast of New Holland etching/engraving, 1773

Over three weeks late in the year 2013, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation presented a three-part television series, The Story of Australian Art. Many viewers will have been impressed by its deployment of numerous art works. It began with the kangaroo painted in Britain by George Stubbs (1724-1806) from animal remains taken back by the 1768–71 expedition of James Cook and Joseph Banks. The image was widely copied by engraving, in various imaginary landscape settings, such as that represented above.

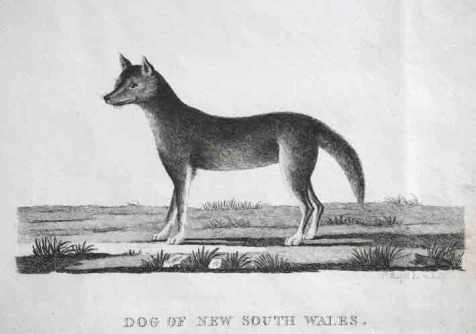

Peter Mazell (pre-1761–c.1797?) Dog of New South Wales engraving Illustration for The Voyage of Governor Phillip to Botany Bay, 1789

Then, after an animated modern parody of an early colonial scene painted in Sydney, we are unaccountably conveyed to Melbourne in the 1880s, and formation of what is known as the Heidelberg School of painters, in a style or styles said to represent Australian Impressionism. In the process the programme omits major developments which took place during the nineteenth century, culminating in the art of Louis Buvelot (1814-88), the first to depict the landscape as recognisably Australian. Buvelot is not the only deplorable omission. The colonial experience encompasses fascination with newly encountered wild-life; adaptation to the climate and environment; and relations with the indigenous population.

The television programme did not consider problems involved in accurate identification of species. For instance: was the dingo related to the fox, or to the wolf? According to opinion it was depicted as akin to either one or the other.

Penal Colony

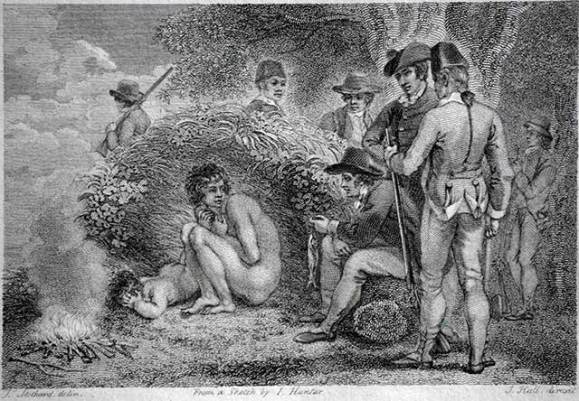

On establishment of a penal colony on Sydney Harbour, treatment of the local inhabitants became a serious matter, considering that their traditional life, territorial ownership and means of livelihood had been seriously disrupted. Yet the programme has no reference to any of the newly discovered bird and animal species nor artists who recorded them, such as naturalist, John Gould.

Thomas Stothard (1755-1834) title-page engraved illustration to Hunter’s Journal after a sketch by Captain John Hunter (of some of his men offering fish to an Aboriginal woman and child)

John Gould (1804-81) Ardetta stagnatilis hand-coloured lithograph (also common to Melanesia: popular names include Nankeen Night Heron, Rufous Night Heron, New Guinea Tiger-heron)

And no mention of Conrad Martens, who had been with Charles Darwin on the Beagle as naturalist artist to the 1831-36 survey expedition. Yet for Australian landscapes Martens reverted to the Picturesque mode of British romantic landscape painting, with attractive scenes viewed through a frame of artfully arranged foreground trees.

Conrad Martens (1801-78) Bush Scene, Illawarra hand-coloured lithograph, 1851

Later, with arrival of professional artists, European prototypes were steadily superseded by recourse to Antipodean nature itself, with artists such as Nicholas Chevalier and Eugène Von Guérard in Victoria frequently accompanying voyages of exploration.

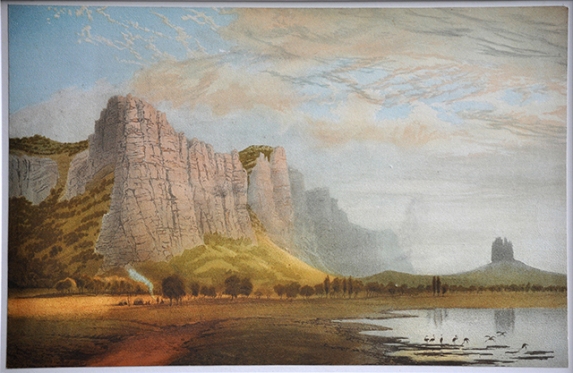

Sometimes they went on joint sketching excursions, with resulting drawings sometimes converted into paintings, and otherwise reproduced as hand-tinted lithographs, or multi-coloured chromo-lithographs – using a technique which Chevalier introduced into Australia. When dealing with hilly country, Chevalier generally chose to depict its features from below, as towering peaks.

Nicholas Chevalier (1828-1902) Mount Arapiles – Sunset chromo-lithograph

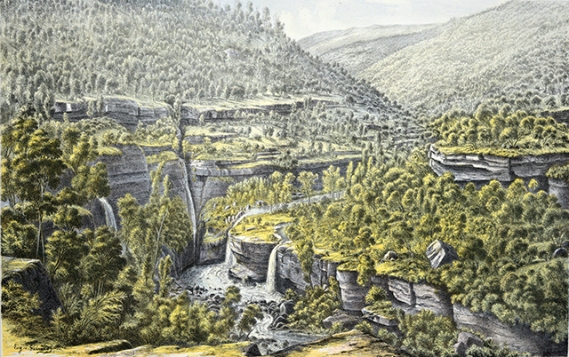

By contrast Von Guérard preferred the panoramic effect of landscape viewed from an elevated location, which tended to diminish incongruously the apparent scale of perceptible objects with increasing distances from his vantage point. For instance, in a scene which he viewed with his colleague Alfred Howitt, he depicted a tiny group of Aborigines in the landscape, though they are hardly noticeable:

Eugène [Eugen] Von Guérard (1811-1901) Moroka River Falls lithograph with duotone tints, 1867

At the time there was a preoccupation with opening up regions “no-one had ever seen before.” A text accompanying the lithograph records that : “. . . they at length reached this romantic spot, and experienced all the gratification which attends the first sight of a magnificent object hitherto unrevealed to human eye.: It is typical of the time that neither he nor Howitt, a pioneer ethnographer , seems to have considered the comment incompatible with the presence of Aborigines in the picture.

Eugène [Eugen] Von Guérard (1811-1901) Moroka River Falls DETAIL lithograph with duotone tints, 1867

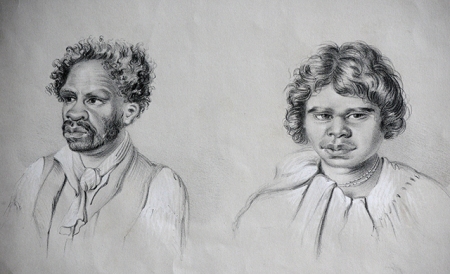

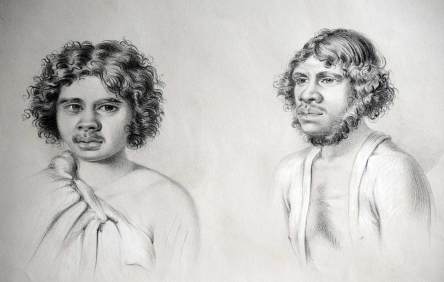

There is no mention of Charles Rodius (a cosmopolitan artist from the school of Jacques-Louis David), who as a convict in Sydney depicted the Aborigines with great dignity, despite portraying them as if imitation Europeans.

After Charles Rodius (1802-1860), Typical Portraits of the Aborigines, (Detail from) lithograph [after images appropriated by George French Angas (1822-86) from drawings by Rodius]

The original drawings still exist from which the opportunistic Adelaide painter and plagiarist George French Angas had this lithographic reproduction made, passing the originals off as his own work. They confirm that Rodius did indeed suggest that some of the indigenous population were adapting to European modes of dress and appearance.

By contrast, in an early phase of Australian sculpture two practitioners in Tasmania were actively depicting Aboriginal subjects. Benjamin Law (1807-1890), created portrait busts from the life, of identifiably significant Aboriginal individuals. The other sculptor, Benjamin Duterrau (1767-1851), who was also a painter, fashioned in low-relief Aboriginal portraits and typically facial expression; besides painting an historical event, The Conciliation – in effect, the end of Aboriginal resistance. Such early beginnings were followed by successive stylistic, technical and thematic developments extending the scope of Australian sculpture.

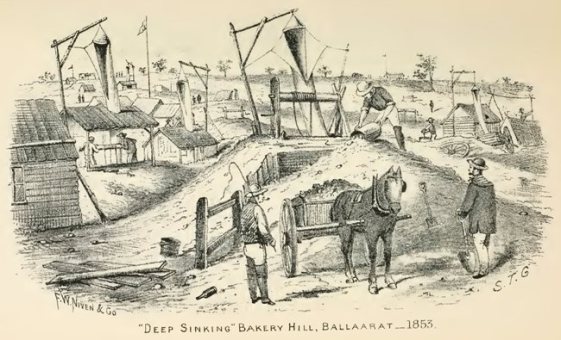

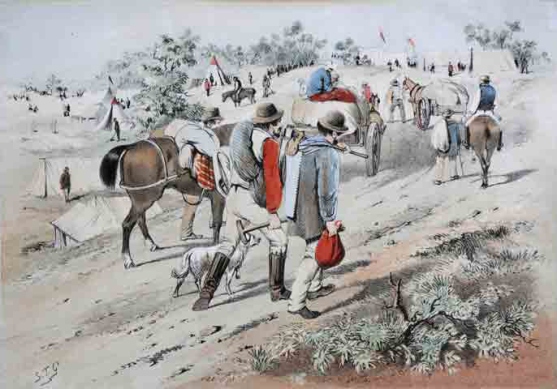

Amazingly, the television series did not include reference to S. T. Gill, who in 1839 abandoned an artistic career in Britain, where he had manifestly been impressed by lively character and caricature drawings by French painter and popular satirist Honoré Daumier (1808-79),whose works were well-known in Britain. Departing with his father for newly-colonised South Australia, he exhibited there successfully, and gained numerous commissions, besides recording everyday life and notable events. But in 1852, frustrated by the plagiarism and privileged status of Angas, he departed for Victoria, where gold had recently been discovered, subsequently producing successive series of lithographs on the Victorian Gold Fields, and their “Diggers.” He spent most of 1856-64 in Sydney, before settling in Melbourne, providing numerous and varied illustrations for an 1870 History of Ballarat – their varying styles and increasing skill probably based on drawings in successive sketchbooks.

Samuel Thomas Gill (1818-80), Deep Sinking Bakery Hill, Ballaarat, lithograph 1853

His illustrations, and “illuminated” capital initials at the start of each chapter, demonstrate his truly remarkable versatility, and lively empathy with colonial and goldfields life.

Samuel Thomas Gill, An example of Illuminated capital D, lithograph, chapter IV, “Digger Hunting”

But his most impressive and popular work is the series of twenty four lithographs published at Melbourne in 1864 as The Australian Sketch-book.

Samuel Thomas Gill (1818-80), The New Rush, lithograph in colours (The Australian Sketchbook, 9 1864)

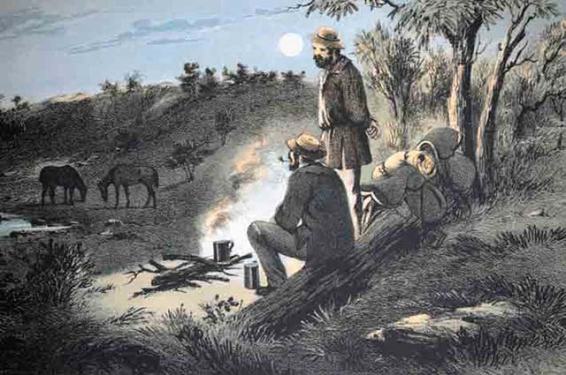

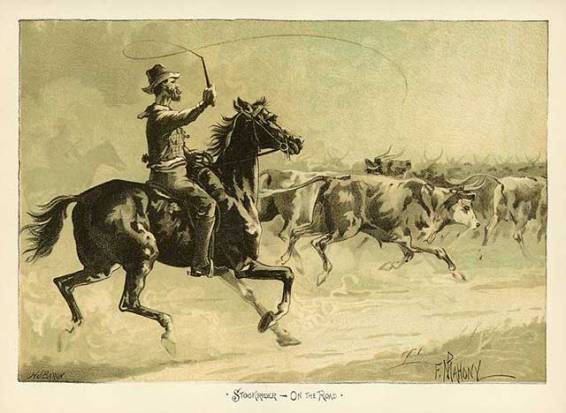

Besides illustrating dramatic results of the discovery of gold, Gill also recorded other socio-economic developments, such as expansion of sheep and cattle farming, creating an extensive droving occupation, and rural Aboriginal employment.

Samuel Thomas Gill, Night Camp, lithograph in colours (The Australian Sketchbook,16 1864)

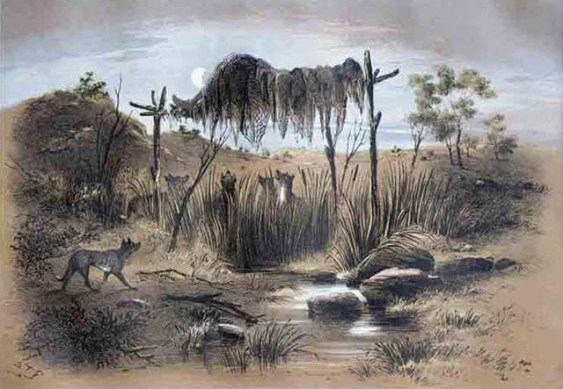

Some of his pictures consequently express horror at the plight of individual Aborigines within his experience. He was among numerous artists who depicted Aboriginal daily and ritual life with respect.

Samuel Thomas Gill, Native Sepulchre, lithograph in colours (The Australian Sketchbook, 17 1864)

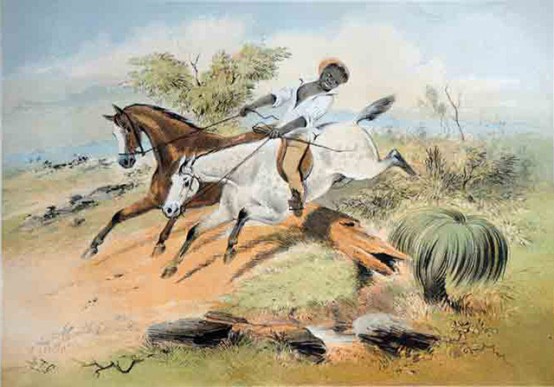

Moreover, he repeatedly depicted friendly cooperation between members of the two communities, and his scorn for those who exploited the indigenous population without compunction.

Samuel Thomas Gill, Squatter’s Tiger, lithograph in colours (The Australian Sketchbook, 23 1864)

Such recognition and illustration of the indigenous culture by numerous notable artists eventually provided a more balanced view of inter-racial relations, conveying much-needed mutual acceptance and understanding.

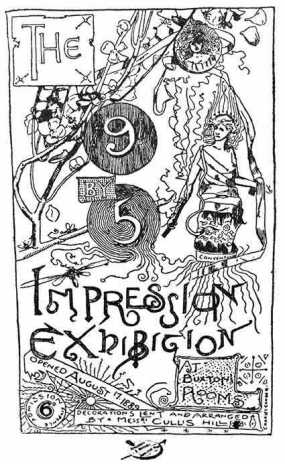

The ABC’s television presentation enthused about Australia’s home-grown Heidelberg School, displaying on camera the catalogue of its 1889 first group activity in Melbourne:

The 9 by 5 Impression Exhibition, catalogue, 1889

This is taken to be the very foundation of what has since become known as the Australian Impressionist Movement. What a pity that the catalogue’s declaration was not spoken on camera: When you draw, form is the important thing; but in painting the first thing to look for is the general impression of colour. Had it been, we might have assumed it to have been written by Monet, Sisley or perhaps Renoir. Not so: it was attributed to G E R O M E, that is, Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904), creator of huge “history” paintings and comparably vast works of surreptitious eroticism; also the copyist, for a fee, of admired paintings in public galleries – and an inveterate opponent of Impressionism, referring to it as “such filth.” To the French President he declared it “The dishonour of France.”

So is someone being devious here? Not at all: the catalogue text uses the word impressionist only to identify an artist who seeks to capture a momentary effect (the catalogue’s impartial term, distinct from the more partisan impression). These small paintings by Roberts, Streeton, Conder, McCubbin and friends were intended to make their art works known to the public through small specimens, not to be a manifesto of artistic radicalism. Attempts to equate these Australians with French artists whose work they hardly knew, if at all, seems a substitute for that television programme’s neglect of Australian art’s nineteenth- century landscape development, culminating in that of Louis Buvelot (1814-88). Seen as a mentor and rôle model by these younger artists, he inspired them with truth to direct experience, as espoused by French landscape painters of the Barbizon School.

Louis Buvelot (1814-88), Summer Evening in the Pentland Hills, chromo-lithograph, 1876

Though Buvelot’s acquaintance with those French painters is often denied, its actuality seems amply confirmed by his manifestly allegorical 1869 painting Waterpool near Coleraine, Sunset, in the National Gallery of Victoria. In it an apparent rural worker walks into the sunset leaving behind the tools of his trade – as no such worker would have done – except for one implement over his shoulder symbolising his commitment to depiction of rural pursuits.

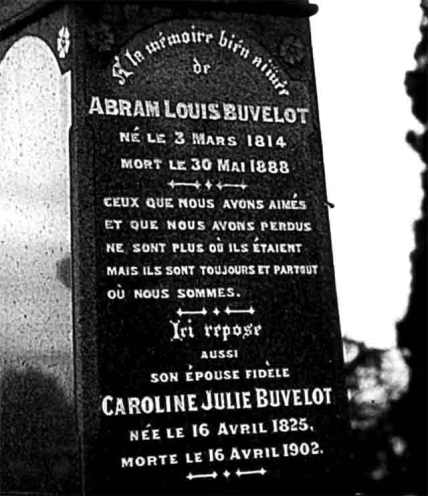

This clearly characterises Théodore Rousseau, a leading Barbizon painter, notice of whose 1867 death had – as confirmed by the State Library of Victoria – reached Melbourne in European art journals, thereby inspiring painting of the picture as an allegorical tribute to Rousseau’s life and artistic integrity. There is a possibly more complex explanation of the sequence of events. Various dates are proposed for another version of the painting (Warrnambool Art Gallery), but its careful execution and absence of the departing figure tend to support established tradition that it was a commissioned copy of the Melbourne original, which in that case could have been before inclusion of the departing figure, as the intended tribute to Rousseau. Madame Buvelot is reported as saying that Louis never painted the same picture twice, which suggests that the occasion may have been treated as a legitimate exception, or subsequently validated by addition of the departing “workman.” After Louis’s demise she found among his papers a note, declaring “Those whom we have loved and whom we have lost are no longer where they were, but forever and wherever we are.” She had the sentiment inscribed in the original French on the monument they subsequently share in Melbourne’s Kew cemetery.

Melbourne, Kew Cemetery, funerary monument of Buvelot and his wife

Disregard of Buvelot is matched by superficial treatment of Tom Roberts (1856-1931). In Shearing the Rams potential eye-contact of the “tar boy” with viewers of the painting is treated as nothing but whimsy. Yet the same work’s “picker-up” seems to have just walked from real space into pictorial space, virtually dissolving the picture plane. This is manifestly inspired by the bronze doors to the Baptistery in Florence, by Lorenzo Ghiberti (1378-1455), known from their plaster-cast in London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, already installed there before arrival in London by Roberts in the early 1880s. Likewise, the horse in Roberts’s painting The Breakaway has seemingly galloped through his studio to get into the landscape just in time to head off the sheep’s wild stampede for alleviation of their thirst. The relevant eye-contact recurs in other works, with three instances in Coming South, which has all the ship’s verticals skewed so viewers seem to share in the sea’s constant surge and swell.

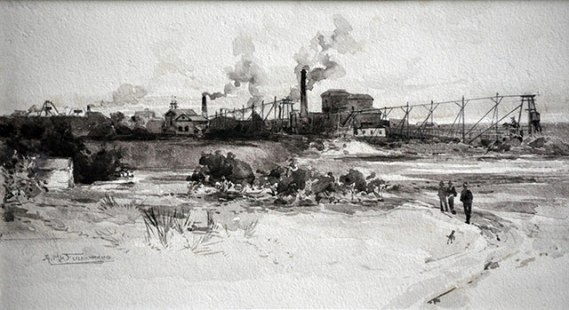

All this appears far more exciting and interesting than any hypothetical commitment to inapplicable dogmas derived from altogether different artistic circumstances. It could be that Roberts’s ideas signifying continuity of real and pictorial space also owed something to Leonardo da Vinci’s note-books, their English translation by Richter having been published in 1883. Yet these and other works by Roberts, such as Bailed up, Bourke Street and The Artists’ Camp, plus comparable paintings by others including Conder, McCubbin and Streeton, owe a great deal to both Gill and Buvelot.There is no reference to the 1788-1888 Centenary of colonisation, as celebrated by publication of The Picturesque Atlas of Australasia, with artists hired to provide illustrations from various parts of the region.

A. Henry Fullwood (1863-1930), Moonta Mines, South Australia, brush drawing for The Picturesque Atlas of Australasia.

which stimulated many artists to adopt such subjects for more formal art works:

Frank P. Mahony (1862-1916), Stockrider – on the Road, lithograph c. 1889?

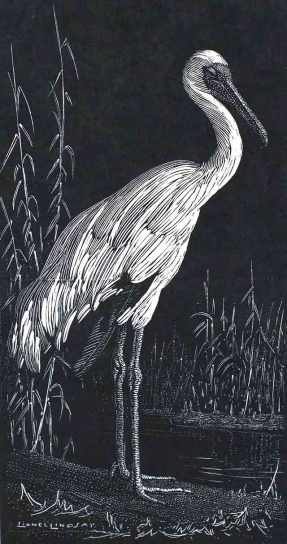

Nor is there any mention of the English Aesthetic Movement, including the influence of Whistler’s subtle atmospheric effects, despite relevant works by such Australians as Syd Long, Lionel Lindsay, Walter Withers and David Davies. Their aesthetic results were often achieved through subdued tonality, plus choice of romantic subject matter, whether of mood, atmospheric conditions, exotic birds, plants and animals; or use of delicate treatment and diminutive scale.

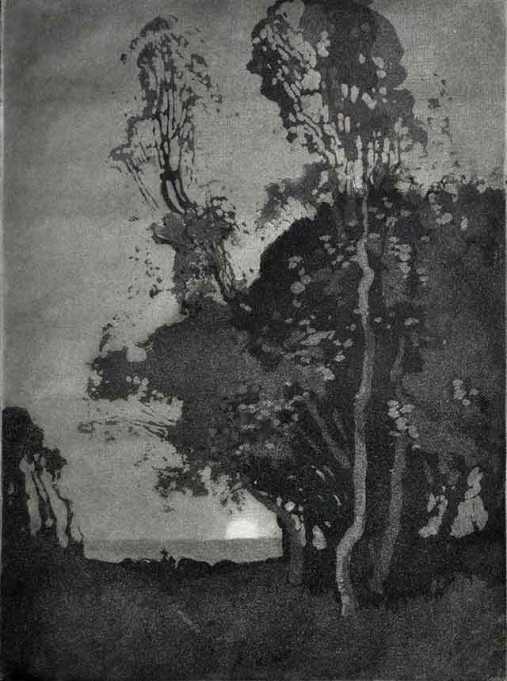

Sydney Long (1871-1955), Moonrise, aquatint

Lionel Lindsay (1874-1961), White Stork, wood-engraving, 1925

The commentary which concentrates on “modernism” as the main twentieth-century trend of the art of Australia is essentially a mainstream view by the presenter, even appropriating photography as a “modernist” rather than universal medium. The actuality is far more diverse — by natural evolution — than that might suggest.

Certainly the limitation to three hours for such a series did not facilitate great differentiation. Still, direct influence of French painting, from Impressionism onwards, developed in Australia mostly throughout the twentieth century — rather than in the nineteenth. Robert Campbell (1902-72), for instance, painted this French street scene of 1930 in a convincingly Impressionist style suggestive of Alfred Sisley (1839-1899), long after it had been superseded in France.

Robert Campbell (1902–72), Suèvres (Loire et Cher), oils,1930

The art schools mainly taught Academic “realism,” with competition from various private courses offered by established artists, among others Max Meldrum, who practised and taught a tonal variant, with reliance on the “edge” of each demarcated area of contrasting tone. Several generations of followers dogmatically perpetuated this manner, especially for portraiture. But there was much variety in the work of migrant artists from sundry nationalities. Though from a Norwegian background, Harald Vike, active in various parts of Australia, brought with him an admiration for the works of Vincent Van Gogh, as in this example-

Harald Vike (1906-87), untitled and undated landscape, oils

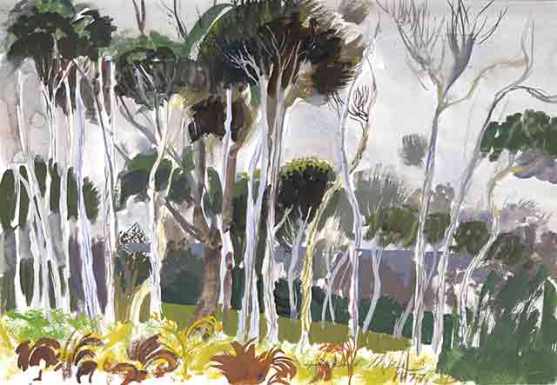

This displays overt admiration for the work of Van Gogh, commonly classified as a “Post-Impressionist,” a term which has more to do with chronology than with style. Yet Harald rapidly responded to local conditions, developing distinctive personal modes of dealing with characteristically Australian subject matter –

Harald Vike, untitled and undated landscape, gouache

In short, the art scene was far more diverse than has been suggested, with many significant artists omitted in consequence. A comprehensive view of the breadth of taste among wealthy art buyers can be gained from the 68-page Catalogue of the 1953 auction for the effects of the late Sir Keith Murdoch. Its Australian component alone encompassed artists as disparate as Henry Burn, McCubbin, Roberts, Conder, Streeton, Constance Stokes, Bunny, Phillips Fox, Gruner, Enid Cambridge, Eric Wilson, Drysdale and Dobell. The total takings were probably more than enough for Keith Murdoch’s son Rupert to buy the Adelaide News, and embark on an extraordinary proprietorial career.

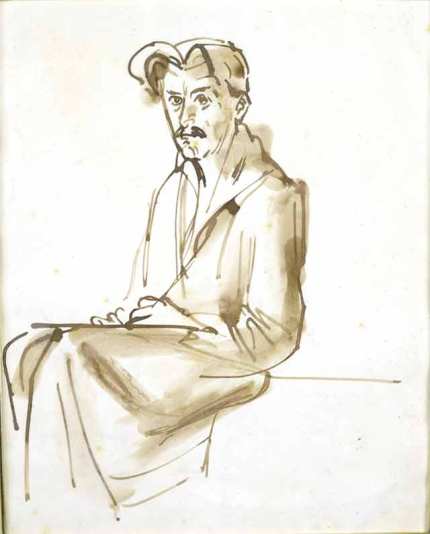

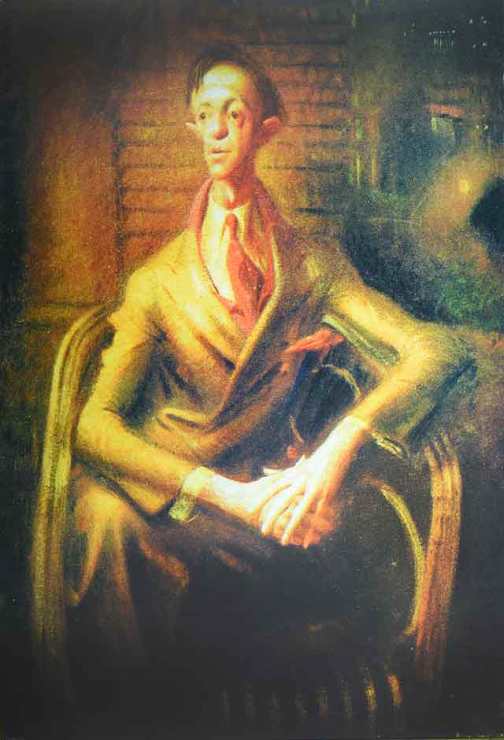

Omission of Australia’s most noteworthy artist of the 20th century, William Dobell, from this series dubbed The Story of Australian Art is astounding. From 1916 to 1924 he was articled to an architect in Newcastle, New South Wales, but his life changed radically with award of a travelling scholarship to study in London. By the time he returned in 1939 he was an accomplished and highly individualistic artist, with a firm conviction of the anomalous status of the dedicated artist in modern society.

William Dobell (1899-1970), self-portrait, ink and wash c. 1932

This feeling of alienation motivated him to paint what he conceived as a portrait of the typical artist of his time, with his fellow artist, Joshua Smith, as sitter, but with the conception based on travesty, hitherto unrecognised, of the serene posture idealised by Leonardo da Vinci for his so-called “Mona Lisa”.

William Dobell, Portrait of Joshua Smith (originally Portrait of an Artist), oils, 1943 (since severely damaged — accidentally — by fire: replica)

Close friends were so impressed that they persuaded Dobell to enter the painting for Sydney’s major art award, The Archibald Prize for Portraiture. Under the competition’s terms the sitter had to be identified by name, so the painting necessarily became Portrait of Joshua Smith.

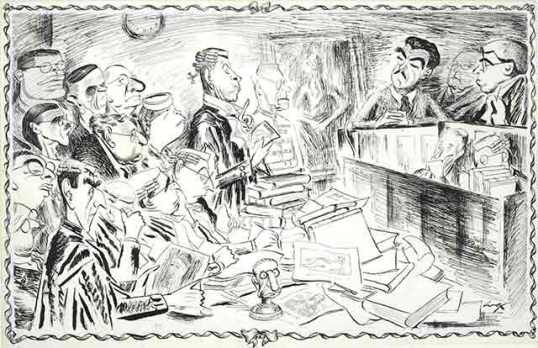

Its award of the prize resulted in heated public debate, with conservative artists and art lovers condemning the painting as a caricature, not a portrait, and initiating a legal challenge before the Supreme Court, formally adopted by the attorney general, as obligatory in Equity proceedings. The case progressed with considerable malice, but was ultimately dismissed by the court on the grounds that portrait and caricature are not mutually exclusive categories.

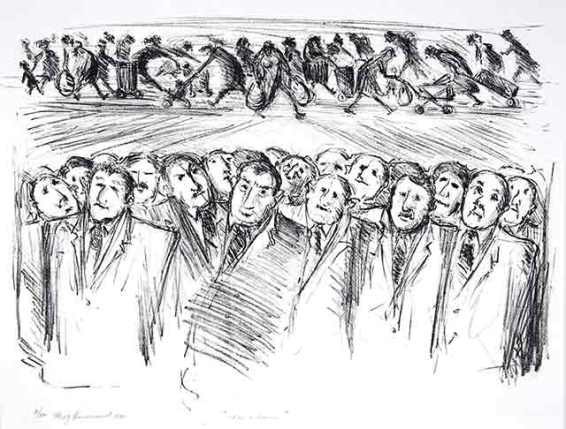

But Joshua was ridiculed in the press, and having been summoned to appear in the proceedings was treated more as an exhibit than a witness. He was so humiliated that he never again spoke to Dobell, his former friend. William Pidgeon, successful as both cartoonist and portraitist, frequented the court, recording the proceedings and depicting participants in images which teeter between popular conceptions of portraiture and caricature.

William Edwin Pidgeon, “WEP” (1909-81), proceedings and participants of the 1945 trial in Equity challenging award to Dobell (for his Portrait of Joshua Smith), of the Archibald Prize for Portraiture, pen and ink drawing, 1945.

Since all participants are easily identifiable in the drawing, the painting likewise does indubitably qualify as portraiture. Its element of exaggeration shares the degree of recognition attainable in photography. Thereby “Wep” anticipates – or perhaps contributes to – the judge’s finding. “Wep” was himself awarded The Archibald Prize for Portraiture in 1958, 1961 and 1968.

By comparison with Dobell, Sidney Nolan seems given undue prominence (gratuitously including a needless account of his private life); though little critical analysis of his works, and of his fashionable stance as a pseudo-primitive. His use of disproportion, divergent perspective, and suspension of gravity among other natural forces are carefully calculated, and show clear awareness of pre-Renaissance art. As a prophet, however, Nolan was late on the scene.

The Sydney Harbour Bridge is prominently featured in the programme, naturally having attracted artists living in the vicinity. But it is not recognised as one of the world’s great marvels, as suggested in the commentary. Like Nolan it was late on the scene. Most of its depictions concentrate on pictorial rather than structural form. To the public it was promoted as a romantic addition to Sydney Harbour, the souvenir trade favouring blue and silver night scenes, with myriad lights reflected in the water. The bridge has latterly been superseded in public acclaim by Sydney Opera House.

The series seems to have favoured a latter-day view that indigenous paintings and carvings were formerly treated as artefacts, and recognised as art only under the influence of abstract north-hemisphere-derived painting’s arrival in Australia. The commentator and his informants could not be more astray: Australian Aboriginal art was praised for its sophisticated artistic qualities in Leonhard Adam’s non pejoratively titled Primitive Art, of 1940, before such opinions were even formed.

Leonhard Adam, Primitive Art, Harmondsworth 1940

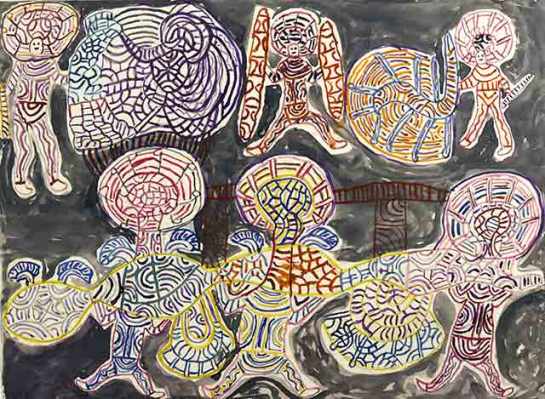

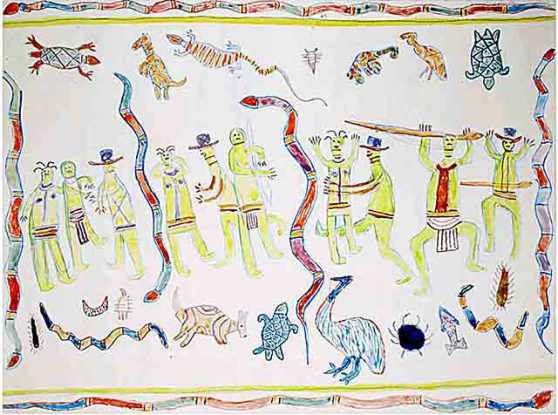

When Laurie Thomas (1915-1974) was organising the 1951 Jubilee Exhibition of Australian Art, he went out of his way to have Aboriginal art included as art, and for Leonhard Adam to contribute to its catalogue his scholarly evaluation of its cultural qualities. The ABC programme mentions works by indigenous artists, but with little detail or insight. The societal importance of the innate Aboriginal urge to create visible and tangible images is attested by autonomous developments in various parts of the country. A virtual trade school for Aboriginal children in south-western Australia instinctively gave rise to an art movement among them, celebrating traditional Aboriginal “belonging” to the country. The phenomenon is celebrated in: Mary Durack Miller, with Florence Rutter, Child Artists of the Australian Bush, London/Sydney 1952 The state government’s response was to close the school “for renovation,” re-opening it later as a “farm school.” Some other young Aborigines, of the Pilbara region, being treated for tuberculosis in a sanatorium near Perth, were befriended by notable artist Guy Grey-Smith, a fellow-patient not long returned from flying for the R.A.F. in World War Two. With the art materials he provided they almost immediately produced works of great ritual, social and artistic significance. This one illustrates some mythic beings of Aboriginal legend –

Anonymous Aboriginal, traditional motifs, watercolour andcrayon, c. 1952

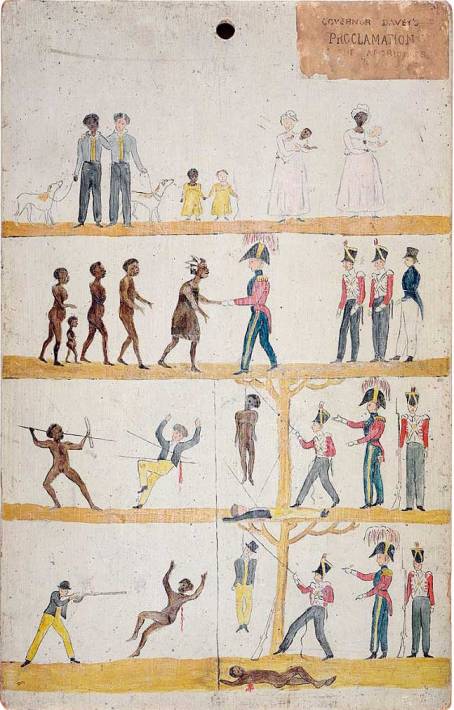

By dramatic contrast, the effect of “episodic pictorial narrative” depicting an inter-racial encounter, and what in retrospect seems its inevitable outcome, has a significance which surpasses even that of the subject’s pictorial treatment.

Anonymous Aboriginal, inter-racial encounter, watercolour and crayon, c. 1952

Though painted in watercolour on cartridge paper, this painting is vitally important evidence of both Aboriginal artistry and its long-term practice as part of a common culture encompassing the entire country – including Tasmania, undeterred by Bass Strait (or possibly preceding its existance) . The evidence is that it matches the kind of Aboriginal episodic narrative paintings seen and emulated by George Frankland (1800- 38), surveyor-general of Tasmania, to represent British law allegedly applied equally to Europeans and Aborigines. His picture was copied on many boards, to be hung on trees, conveying that message to the Aboriginal population, in the aftermath of the so-called “Black War.”

after George Frankland (1800-1838), painted message board.

The distance between Tasmania and the north-west of Western Australia — and their separation by the full extent of the mainland plus Bass Strait indicates the widespread nature and long duration of Aboriginal tradition, as conveyed by the painting style’s functional intelligibility at opposite extremities of Australia, encompassing its intervening ocean. In seeking the 1952 picture’s inclusion in a sale of indigenous art, the art-auction industry stressed its numerous important features — exactly the reasons they were given for its perpetual retention in the public domain.

There is recent renewed support for acknowledgement in the federal Constitution, of Australia’s original inhabitants. This irrefutable evidence of the long-term existence of our indigenous fellow-citizens to a single coherent culture is ample justification for implementation of that long-overdue constitutional reform, without demur or further delay. Its basis should include input by those whose future is directly involved, and with their understanding and approval—by contrast with the arbitrary and coercive federal “Intervention” of several governments ago.

Artistically talented indigenous individuals have occasionally had their potential recognised by rural workers and brought to the notice of officialdom – sometimes with beneficial results. Various well-known artists besides Guy Grey-Smith have at times identified with indigenous culture, and encouraged its development. Elizabeth Durack for example was inducted into a community in the north of Western Australia, her membership according her a classificatory maternal relationship with some younger members. So intense was her self-identification as a community member that she felt increasingly possessed by a powerfully conceptualised Aboriginal artist, “Eddie Burrup,” and painting in his assumed persona (recounted by Robert Smith, “The Incarnations of Eddie Burrup,” Art Monthly Australia, 97, March 1997, 4-5).

Elizabeth Durack (1915-2000) — in the persona of “Eddie Burrup” -Catching Stars, oils 1999

Her works (not only those in the persona of Eddie), and writings by her author-sister, Mary — sometimes in collaboration — have done a great deal to improve inter-racial relationships, through their personal sense of empathy with other peoples. Often it is not noted that art history, and the wider cultural history, are indivisible aspects of history in general, and ought likewise to be treated synoptically and contextually. Fashion, style and delusory personal ambition should not be permitted to dominate or distort the integral relationship which all elements of the wider community need to share.

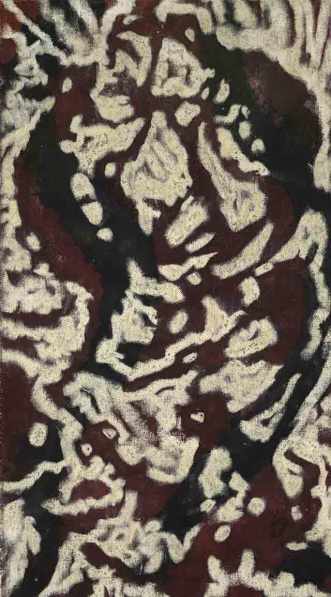

This puts a corresponding burden on serious practitioners and exponents of the arts -which experience corroborates as a burden which most share willingly. From witnessing the third phase of The Story of Australian Art, the public would be justified in thinking that Australia had no committed art – despite a fleeting reference to turmoil created by involvement with the war in Vietnam. The ABC’s dominant theme became the predominance of innovation on the basis of supposed persistence of abstraction. So a painter acclaimed as pre-eminent in this stage of the account, Ian Fairweather, is said to have introduced us to abstract painting. This regardless of the fact that his works are all visually referential, with figural motifs prominent.

Ian Fairweather (1891–1974), Epiphany, synthetic polymer, 1962

Those who can not concede the presence of human figures throughout Fairweather’s work have simply not investigated its significance. Along with this unjustifiable indifference is the assertion by individuals who would not know, that Fairweather was a recluse, living on Queensland’s Bribie Island in huts he had built, and shunning human society. On the contrary, he just did not like the hurly-burly of mechanised life in big cities. On the island, he fraternised with the blokes at the local pub, and attended movie screenings, though confessing that he disliked American films. Near his home he had propped up the trunk of a fallen tree which had developed a curiously almost circular configuration, reminiscent of the Greek letter Omega and was delighted to have it recognised as his version of a Chinese moon-gate – a symbolic welcome to visitors. Those who want to see what a moon-gate looks like should seek among Australian early twentieth century weatherboard houses. The moon-gate, consciously derived from Chinese tradition with which Fairweather was thoroughly conversant, leads to a house’s front door, usually through a latticework- enclosed verandah.

A standard reference on Fairweather’s works comments on this Epiphany in conventional modernist terms as “over-literal,” then proceeds to describe it as “a work operating on only one level . “Reading from left to right we see the vindictive King Herod, the apprehensive holy family. And the three wise bearded wise men larger than Christ; the foetal figures in the cells below are the young children, the future generations, about to be slain.” Since that sheds very little light on either Fairweather’s painting or the biblical account, the picture can hardly be described accurately as “operating on only one level,” which seems like a conventional pro-abstractionist knee-jerk reaction. What on earth would Herod have been doing at the Epiphany, the biblical origin of a church festival celebrating manifestation of the Christ Child to the Magi, symbolising the three continents then known to Europeans; and the three ages of man. Each representative is unsurprisingly claimed to be larger than the new-born infant, whose message is due for their transmission to the foetal future generations at the base of the picture—not about to be slain! Herod was busy elsewhere, with Massacre of the Innocents, in a failed attempt to kill the one new-born male—Jesus.

When Fairweather’s paintings, always based on themes rather than appearances, were said to have become abstract, he expressed a preference to deem them “soliloquies.” In fact, though often deemed “calligraphic” they do not at all resemble handwriting, even in its Chinese manifestation; the development being from the primitive phase of pictography (pictorial communication), to its mature and sophisticated development into ideography – embodiment of mental concepts – Fairweather’s subliminal motivation.

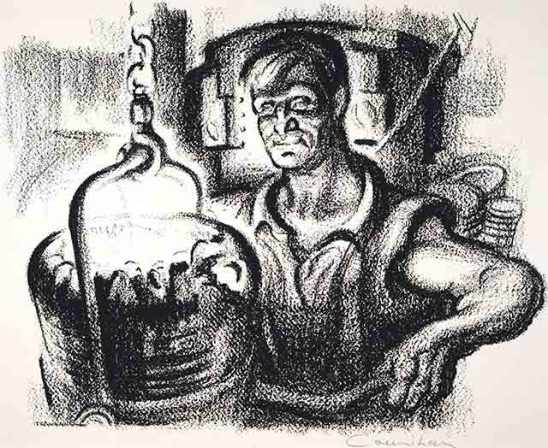

Some of the paintings bear titles he conferred; others clearly originate with dealers. The Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery acquired one named Reclining Figure, which a reviewer termed “a giantess dominating the landscape.” Gallery staff found that incongruously unconvincing, until pertinently advised it should be hung vertically, not horizontally. Thereupon it was revealed to be a kneeling woman dressing her hair – a favourite Fairweather motif! There remain many artists beyond the scope of what we witnessed on ABC television, some of them in families or dynasties, such as the Boyds, Dysons, Heysens and Lindsays. Then there are notable individualists, who follow their personal persuasions, including choice of medium suited to their conceptions. An outstanding example is Noel Counihan (1913-1986), who in a career dedicated to material equity and social justice, produced striking figural images to do with respect for physical toil, condemnation of iniquity, and aspirations for progress towards a better and more rewarding life.

Noel Counihan (1913-86), A Metal Pourer, photographic screenprint, 1948

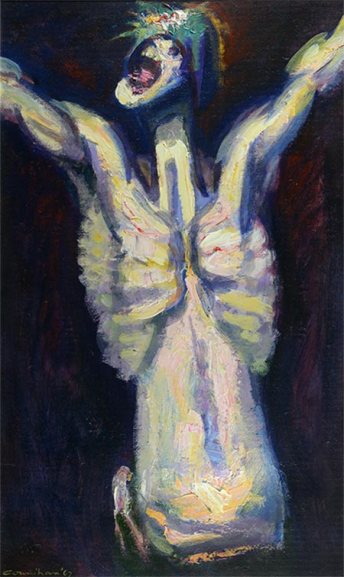

His response to the Vietnam war as morally reprehensible was deeply felt the more so because his two sons were liable to military conscription under the randomness of a lottery of birthdates. Among his initial reactions was cryptic allusion to the Crucifixion as a powerful symbol, perhaps through reminiscence of his time as a choirboy in Melbourne’s Anglican cathedral:

Noel Counihan, Study for Boy in Helmet iv, acrylics, 1967

More potently, he produced in the contrasting media of brush drawing, oils, and linocut, three variants on the theme of Boy – as militarised, with the risk of decline into unacceptable, characteristically male, anti-social atttudes. Other free spirits include Godfrey Miller (1893-1964), with a unique painterly technique often employed to support an assertive civic conscience; and Peter Purves Smith (1912-1949), whose satiric irony readily deflated pomposity, conformity to military discipline, and assertions of racial superiority. The case for Australian art has been made thus far on the basis of two dimensional works. In admirable token representation of three dimensional art, what could be more apt than materialisation of Miguel de Cervantes’ creation of that whimsical hero, Don Quixote, in George Luke’s three-dimensional realisation of wayward rider and scrawny but stalwart steed.

George Luke (1920– ? ), Don Quixote, ciment fondu with bronze lacquer finish c. 1960

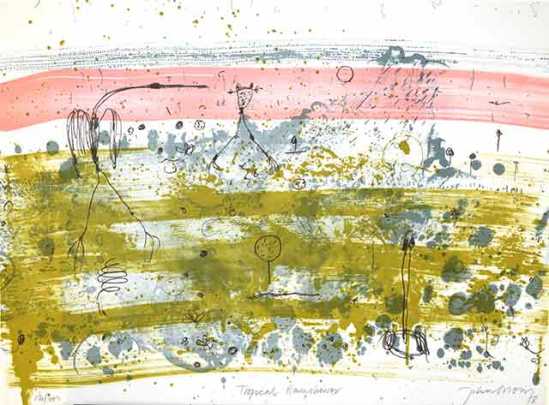

Much modernist Australian art has developed distinct regional characteristics, with perhaps the most notable contrast between particular trends in Sydney and Melbourne. John Olsen finds phenomena in nature justifying his preference for an impulsively free “Sydney” style complying with the local partiality for “abstraction,”enhanced ironically by whimsically juvenile jottings.

John Olsen (1928–), Tropical Rainshower, lithograph (Bodford Terrace Folio, 1978)

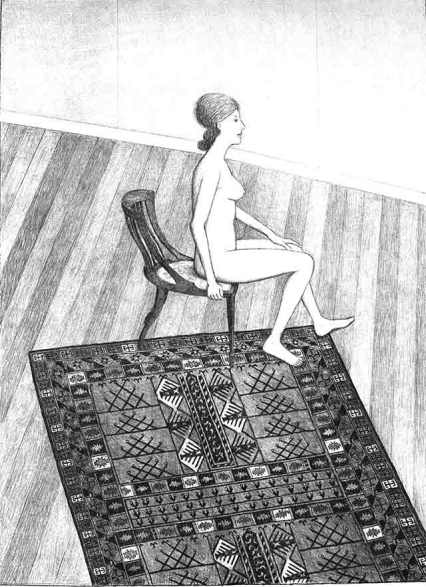

By contrast, John Brack bases ironic themes typical of self-conscious Melbourne culture on aspects of social life – including a “life-class” study of the female nude – in an interior deliberately asymmetrical by design, not nature.

John Brack (1920-99), Nude in Profile, lithograph (Bodford Terrace Folio, 1978)

In conclusion, and further token acknowledgement of contributions to the story of Australia’s art in this case by women artists – here is a wry comment by Mary Hammond on the preoccupations and compulsions of men and women in their respective – and sometimes frenzied – everyday activities.

Mary Hammond (1928-), Men and Women, lithograph 1989

Even within regrettably unavoidable limitations the actual story of Australian art is an enthralling pageant of observation, interpretation and celebration of the unique and multifarious Antipodean experience, as captured by several centuries of oddly assorted artists.

Yet the ABC programme’s comments on modern Australian art are laced with such expressions as “a sense of cultural inferiority” from which, apparently, “Australian art was set free” by some favoured form of art. In the commentary many a journalistic beat-up is enthused over as having universal significance, such as being the world’s most ancient, largest or only: as if they are valid criteria. With innovation as the ruling factor, artists in the television account replaced one another in prominence with confusing rapidity, while many an artist of integrity and perseverance is omitted. Thus William Dobell, long pre-eminent for artistic originality and integrity, as aforesaid does not rank a mention – despite being the butt in 1944 of that rabidly anti-modernist art trial.

The farce reaches its apotheosis with the 1968 Melbourne opening of the National Gallery of Victoria’s new building, with a celebratory exhibition. Its title, The Field, was an allusion to the Melbourne Cup – as if there could be only one winner in the art stakes. The Premier, Henry Bolte, was fresh from his “victory” in having had convicted murderer Ronald Ryan hanged in Pentridge Jail despite organised opposition to capital punishment. He looked on the new building as another of his achievements. He, not some minor British royal, was going to have the honour of declaring it open. Gallery director Eric Westbrook and his staff had taken great pains with The Field exhibition, but to little avail. This was very much a social and political, not a cultural occasion, with Henry defending “his” building against journalistic criticism which likened its external appearance to that of Pentridge Jail.

The climax came with The Premiers announcement: “Not only does it not look like Pentridge Jail – there’s a lot more hanging space.” There was a collective gasp of disbelief, and diminutive Arthur Boyd, who for a better view was standing on a chair near me, nearly fell off it in amazement and shock.

But in terms of the economy there is no inevitable conflict between culture and its wider social concomitants, even those of the art industry. Yet in the aftermath, art commentary has become excessively geared to market movements; and much art collecting to prospective financial appreciation. We have yet to recover, if at all, from that malaise.

Robert Smith 2015